Beauty, Truth, or Goodness? In a previous article I wrote called 'Twilight of the Idols', we learned (from Nietzsche) that truth is not a useful concept to designers and structural engineers. Let science (or religion, for that matter), have ownership of truth. We can do 'truth' in our spare time. We also have learned (from manifesto on goals being useless), that beauty is a by-product of our work, not something we need to consciously drive towards. What is left? Goodness. Quality. We should focus in this arena of Plato's Trinity, not the other two.

We design buildings, bridges and other structures, but how do we do this well or how do we improve over time? Does our conception of the structure to be built change with experience and improve? Yes, we learn what is feasible and what is practical with experience but what about Quality? When we develop options for consideration or make a decision based on a certain amount of information, how do we choose the best option and make the best decision?

The entries in the Manifesto blog herein, are some attempts at improving design, and many others have written on the subject for structural engineers. For example, David Billington in The Tower and the Bridge, described how the best designers of the past made engineering decisions based on a balance of efficiency, economy and elegance. We can add to those considerations such as durability, constructability along with resilience and sustainability. Also, when thinking about quality, we can do this in two ways, the end (the structure itself), and the process (the design process). We can say to ourselves “I want quality in the form of the structure and the assemblage of materials” or “I want to design well, I want to be good at engineering decision making”. These may overlap. For example, how does the description or idea of the final artifact as “quality”, create a path for working towards it? After all, we are typically designing new and novel things (i.e.. not pancakes that we can taste, recook and/or adjust ingredients easily).

In may be worth investigating what the Philosophers of antiquity thought on the subject of quality, beauty, and art. I found that a terrific anthology to get a good background on this subject is Hofstadter’s Philosophies of Art and Beauty: Selected Readings in Aesthetics from Plato to Heidegger. In it we find the beginnings of our conception of quality. For example, we find that Aristotle, in his Parts of Animals Book I believes that one has to have a clear picture of the structure first (the end), and simply work towards that.

He starts by forming for himself a definite picture, in the one case perceptible to the mind, in the other sense of his end – the builder of a house – and this he holds forward as the reason and explanation of each subsequent step he takes. Art indeed consists in the conception of the result to be produced before its realization in material... The plan of the house has this or that form; and because it has this or that form, the construction is carried out in this or that manner. For the process of evolution is for the sake of the thing finally evolved, and not this for the sake of the process. (Aristotle, Parts of Animals Book I, 640).

But how does one conceive of an end first? How does one know ahead of time that something will be good, correct and well proportioned or efficient and economical? Here we learn from Aristotle, that good design is done by those who can take a complex task and split it up into smaller and simpler problems. One step at a time. Engineers are pretty skilled at this. It may also be that when a good engineer has a vision, or an end to be aimed at, he/she has a command of measure (what we now may think of as proportion). The engineer, according to Plato, must know the nature of measure for the proper portioning of structures (artistic as well as scientific). Measure for Plato, is essential to quality and is the fundamental principle that defines quality. A column should be this size, not that, for many reasons.

Basic to any art, is the art of measure without which there can be no art at all. For to know the proper size of a column, proportion of a window, the proper organization of language in a poem, is to command the art of measurement.... There are accomplished men, Socrates, who say…the art of measurement is universal, and has to do with all things.” (Plato, Statesman 285b)

So if we think we succeeded in the proper form by creating something well proportioned, how do we know we are right? How do we judge quality?

Every art does its work well – by looking to the intermediate and judging its work by this standard. (Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics Book II 1106)

He agrees that the science may have a hand in the judgment of art.

The chief forms of beauty are order and symmetry and definiteness, which the mathematical sciences demonstrate in a special degree. (Aristotle, Metaphysics Book XIII 1078)

So we can learn a bit about what Aristotle and Plato thought about how to conceive and judge quality structures, but we have learned less about the individual engineering designer. It is the engineer's personal ability that contributes to great work. The engineer that seeks personal excellence will see that transcend themselves and into the built world. It may be obvious that all designers aim for quality structures as Aristotle suggests in his opening to Nicomachean Ethics.

Every art and every inquiry, and similarly every action and pursuit, is thought to aim at some good; and for this reason the good has rightly been declared to be that which all things aim. (Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics Book I 1094).

And to which all engineers should aim - but not aim towards goodness, it is not a goal, it is a way. Here we are back to the process of design, how the individual designer takes action and aims at some good, or quality (and being good is integral to this, but not going there). It a process that requires constant reflection and the way to create safe, economical and efficient structures and do it better and better over time.

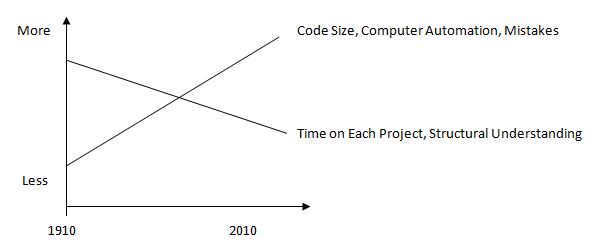

We know that the design of structures combines the objective science (material mechanics) with more complex subjective decision making requiring sound judgment (heuristics). Problems encountered by the structural engineer are complex and nuanced and require experience and judgment to better sift through the multiple design ideas. If you have been reading this blog, one recurring theme is that idea that engineering is more of an art than a science. Not art as beauty or aesthetic vision, not at all. Again, that is useless. In the forward to Nervi’s book Structures, Mario Salvadori says it best when describing one of the greatest structural engineers of the 20th century:

Nervi’s results are not achieved by consciously trying to meet aesthetic demands, but by tackling the fundamental structural problems from the outset, and giving them an obvious and clearly articulated solution. Beauty, says Nervi, is an unavoidable by-product of this search for satisfactory structural solutions. [Salvadori 1956: vi]

So no answers or short cuts to quality, just more questions. The original of my poem on Nervi called "The Structure That Sings" (later published in STRUCTURE) has a similar conclusion (beauty as an end and not sought after)...

There is something called "design science" (bio-mimicry, form finding, geodesic geometry, etc) which has mathematical, scientific, and objective procedures to create form. So "truth in form" is okay - but again, it is very rare that good design is driven by scientific methods. It can be, but more often not. So, if I could re-write this, I would replace "truth in form as a means", with "quality as the means". Quality, is by definition, process. As Pirsig would say, quality is "the knife edge of experience", and living in it and with it, beauty just becomes.